More New Yorkers are surviving sepsis. What happens when they leave the hospital?

In Sepsis

Get Dexur’s Personalized Hospital Specific Presentation on Quality, Safety, Compliance & Education

By: James Pitt Mar. 28, 2019

Sepsis contributes to up to half of in-hospital deaths. New York State launched the Sepsis Care Improvement Initiative in 2014, after the tragic death of 12-year-old Rory Staunton in Queens.

It's working. Sepsis is killing fewer children and adults at New York hospitals.

But the story doesn't end when a patient leaves the hospital. Nationally, close to a third of sepsis survivors have to return to the hospital within 30 days of leaving.

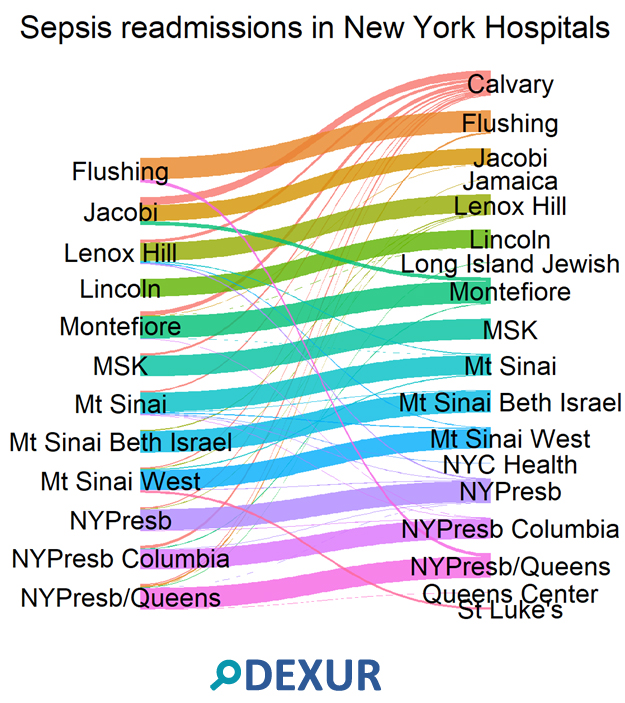

"Readmission risk after severe sepsis varies dramatically across hospitals," says Perelman School of Medicine professor Mark E. Mikkelsen. Dexur analysts found that at the largest hospitals in New York City, most of these patients return to the hospital that initially treated them.

But many don't. Compare Montefiore and Jacobi Medical Center. Sepsis patients from these hospitals have similar readmission rates, 28% at Montefiore and 29% at Jacobi. (These numbers come from 2013-2017 Medicare claims data). But patients initially treated at Montefiore were much more likely to return there on readmission than patients initially treated at Jacobi.

Patients tend to be readmitted uptown from the hospital that initially treated them. For example, patients treated at New York Presbyterian/ Columbia University Medical Center were more likely to be readmitted in the Bronx than in lower Manhattan.

Readmissions weren't symmetrical. Calvary Hospital serves as an important catchment area. Calvary reported fewer than 11 readmissions among Medicare inpatients with sepsis from 2013-2017. But sepsis patients from other hospitals often went to Calvary on readmission. It was the most common destination for sepsis patients from New York Presbyterian/ Columbia; Memorial Sloan Kettering; and Mt. Sinai.

Sepsis is now the leading cause of 30-day readmissions in the United States. Outcomes for readmitted patients are often poor, and fragmented care can exacerbate this. Helping hospitals trace where their patients go may help them provide better care.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR